Scot Buzza is an author for the A-R Music Anthology. He has written two commentaries on works by Giovanni Gabrieli, with further contributions on the way. Like many musicologists, Scot has had a diverse career. He started out as a performer, holding the position of principal violist in the Tokyo Philharmonic and later in the Chamber Orchestra of Barcelona, Spain. He returned to the US to pursue choral conducting, which then led him to the field of musicology. Scot currently teaches music history and music theory courses at Northern Kentucky University for majors and non-majors. He also runs and teaches at the KIIS Institute, a study abroad consortium located in Salzburg, Austria.

We recently sat down with Scot to talk about how he is using the A-R Music Anthology in the classroom. It turns out that ARMA is an excellent companion for his non-chronological music history class for non-music majors. Keep reading to learn more!

Questions & Answers

Do you use the Anthology or other digital teaching resources for any of your classes?

Yeah. I’ve used it with my non-music major history class, with actually two permutations of that. One is college students, and a second is high school seniors taking college classes for college credit as an exploratory kind of thing. The syllabus that you saw, where I’ve organized things by topic rather than chronologically, that’s for that non-major class.

The department wanted something that would satisfy elements of the core curriculum and not be something as watered down as a music appreciation class, which I don’t know if anybody really takes that seriously in the real world. Something with a little more substance, but what we could not count on was having students that are musically literate. Some of them come in and they’ve been playing in band since junior high school and they’re fine when you put print music in front of them. Others are not. And so that’s where the design came from. In fact, it says amongst the prerequisites that music literacy a requirement, even though it’s certainly very helpful. The first class we just go over vocabulary to make sure everybody’s on board. Lots of people who are fairly competent at self-taught musicians get lost in the Italian vocabulary. The only kind of preparatory thing for that is a quick crash-course in “this is what a crescendo is,” “this is what timbre means,” because that’s the vocabulary that they need in order to make sense of the rest of the material.

What made you decide to investigate using digital resources and the Anthology, in particular?

COVID. I’ve probably taught the first semester of Music History—it’s a three-semester sequence, so we’re talking about basically Fred Flintstone up to the beginning of opera. That whole chunk there, which is the hardest to teach. It’s the hardest to learn. It’s the most foreign to the students, and they’re the least familiar with it, because this isn’t the repertoire that they’re singing in choir or studying in their lessons.

I had noticed a couple of things over the years. One is that if I required them to buy an Anthology, half of them didn’t buy it. The half that did rarely brought it to class. When they did bring it to class, just by virtue of using it, if we’re trying to do score study, the students have their faces in the score. They’re semi-disengaged. I’m talking at them, checking for signs of life, not sure whether people are following along or not. So I had already stopped using a print anthology and was kind of stumbling through using a mix of stuff that’s public domain, stuff that I could reasonably use under fair-use, and projecting it on the wall. Even if their brains were checked out, at least their visual field was clued into what was going on. The big points of teaching that particular semester of music history aren’t to run away with a catalog knowledge of everything that Josquin ever wrote. The idea is to come up with a general understanding of how polyphony happened, how music notation happened, how the human perception of dissonance and consonance changed and evolved over the years. It’s those big milestones, and you have to do score study. In order to do that, you cannot possibly get a sufficient understanding of that just by talking it or reading about it in some dry text.

The other thing that I noticed was that there are various music history textbooks on the market—some I like better; some I don’t like quite as much. Most of them are more than students seem to be willing to ready on a regular basis. I almost had to teach every class as if nobody had done the reading, and that was tedious. So by substituting videos, including stuff like YouTube or stuff that I could create myself—podcasts, recordings of concerts, filmed concerts, and things like that—I could cut the reading part down to about 1/5 of what it was, which meant that students were more likely to do it. And when it comes down to it, do I really need to assign a six-page reading about Roman de Fauvel? No, I would rather have them take 30 minutes and listen to some of the pieces from it and read a short commentary on it to understand how the music that they’re looking at connects to everything else we’re talking about. The score study component is just so crucial, especially for that particular semester of music history.

One of the benefits, then, of using digital resources is you can pick and choose more carefully what you want your students to focus on?

Exactly. And the big beauty, as far as I’m concerned, with the A-R Anthology is precisely that. You can cherrypick. I’m not stuck with a specific canon. For years, everybody that went through Music History 1 had learned the same 36 pieces of music. I understand why it is that way, but those aren’t necessarily the best representative pieces. We can say that in the year 2021, having had 30 more years of scholarship behind us than we had in 1991, for example. A print anthology is going to be limited between two covers. That’s the nature of a print book. A digital resource, especially one that is continually growing—if there is something that needs to be in there that I really want to use, I can write it myself, and then there it is.

I just don’t see a day anywhere in the near future where students are going to want to start having books in their hands suddenly again. I think we turned a corner with COVID, and we’ve learned a lot more about teaching online and teaching with digital resources in the past year and a half than we ever thought we’d have to. And I just don’t see a day where people are going to say I really want to carry around this brick for a semester.

When you are using the Anthology for your college non-music majors and that high school class, do you have the score on a large monitor? How does that part work?

I tend to not do the listening parts in class, because that eats up a ton of class time and students will check out. I tend to give them a road map: check for this, check for this. If I do something in class, I might flash the score up for two or three minutes and say, by the way, check this out and notice this feature, and we talked about this and here’s an example of it. If you start doing all of the listening in class, you get dangerously close to music appreciation again. It’s just far too passive for students, and the teacher ends up doing all the work. If they have a specific set of focused questions they’ve got to answer about a specific piece of music, they go home, they listen to it with intent, and the onus is on them. And they come out way ahead as opposed to this old paradigm where the teacher babbles on and fills these empty vessels with his infinite wisdom and sends them forth into the world. That paradigm is passed.

Speaking of teaching for non-music majors, can you just talk a little about why you came up with your non-chronological music history course?

I think the beginning of it had to do with how my brain happens to work. True confession, as an undergrad, I never had a music history course. I was a quick study and I always tested out even though I knew next to nothing about it. What I found later on was that I wasn’t content just studying a Bach viola da gamba sonata. I wanted to know how he wrote it, how it compared to the other pieces that he wrote, where he was when he wrote it, why did he write it in this octave and not this other octave, what instruments were performing along with it. I felt that I needed to know the full picture. I felt that I needed to know all of the extra-musical stuff as well. Not biographical anecdotes, because those tend to be—the cuter and quainter they are, the less true they’re likely to be, right? But the economics—what was Bach’s job like at this time, what was expected of him? What was going in the town he was working in economically that they couldn’t pay him better? What was the concept of education that they were hoisting 14-year-old Latin students on him? So all of this kind of stuff.

I came to the conclusion myself—I didn’t realize that plenty of other people have said this far better and far sooner—but I came to the conclusion on my own that there was no point in studying music history without also studying what’s going on socially, what’s going on economically, what’s going on politically. Religion—you cannot teach the first semester of music history without talking a ton about religion, because the two things are just so intertwined. All of that, as far I as was concerned, was important.

If I’m going to teach a music history course to non-majors, I have an overt goal and a secret goal. The overt goal is for them to understand better how music reflects everything else that is going on at the same time. The secret goal is for them to fall in love with these pieces. The best compliment that I ever get is when somebody out of the blue says, “Oh, I still have this on my playlist, and I was listening to Machaut last week.” That actually happens once in a blue moon. Okay, maybe I’ve done my job.

My understanding is that the peripheral stuff shouldn’t be peripheral, it should also be part of the picture. In a one-semester course, you don’t always get to get to that with music majors, especially if you need to focus on harmonic development, or look at what’s going on here in terms of instrumentation. But if you have permission to leave that aside, because they can’t read music, for example, well, how did the industrial revolution influence it? What would have happened if child labor hadn’t been a thing? Etcetera, etcetera. And all that stuff becomes part of the discussion. For students, it becomes intertwined with their understanding of music history. Since it’s something that they are already familiar with, they grasp onto it.

The goal isn’t to make professional-level musicians out of them. The goal is to make them better lawyers and doctors and trash collectors and teachers and whatever else they do.

Can you share some specific examples from your course?

The syllabus, as you saw, I tied it into themes. I organized a general theme, tied it into a specific genre of music, tied that into one or two tangential ideas about what’s going on in the world, just for the visual people in the room, tied into usually at least one work of art that was from the period that somehow ties in. At no point did I ever say that I really want you to fall in love with Mozart Requiem. I just sort of hoped that I would happen.

Here are just four examples:

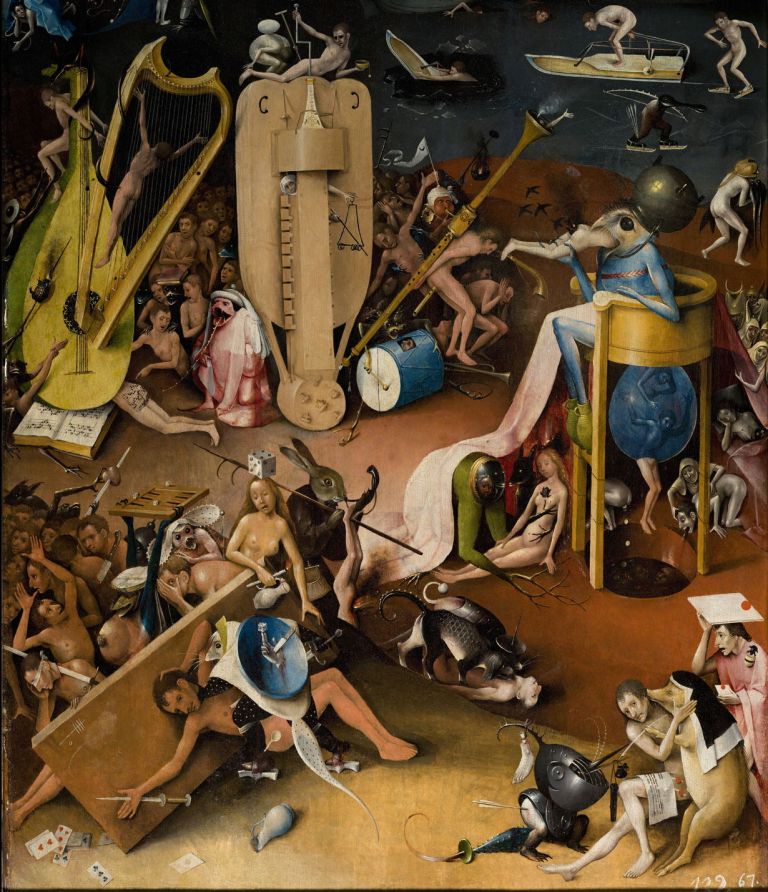

The one chapter that they did, I titled it “Lust, Greed, Earthly Pleasure, and Earthly Pain—just because I love the way that sounded—where they are talking about Italian madrigal as a genre. Looking at 16th-century representations of basically the secular world and the sacred world, worldly pleasure versus Christian austerity. The goal is to try to figure out what those things tells us about domestic life and socio-economic class in the 16th century, and to find out what those things tell us about music making in the 16th century. Madrigals are short, so I was able to tie it into five different kind of representative madrigals—and you probably know all of these— The music was the way into the discussion for talking about the other things. The Garden of Earthly Delights, that nightmarish Bosch painting, was the painting we tied into. So that was one chapter.

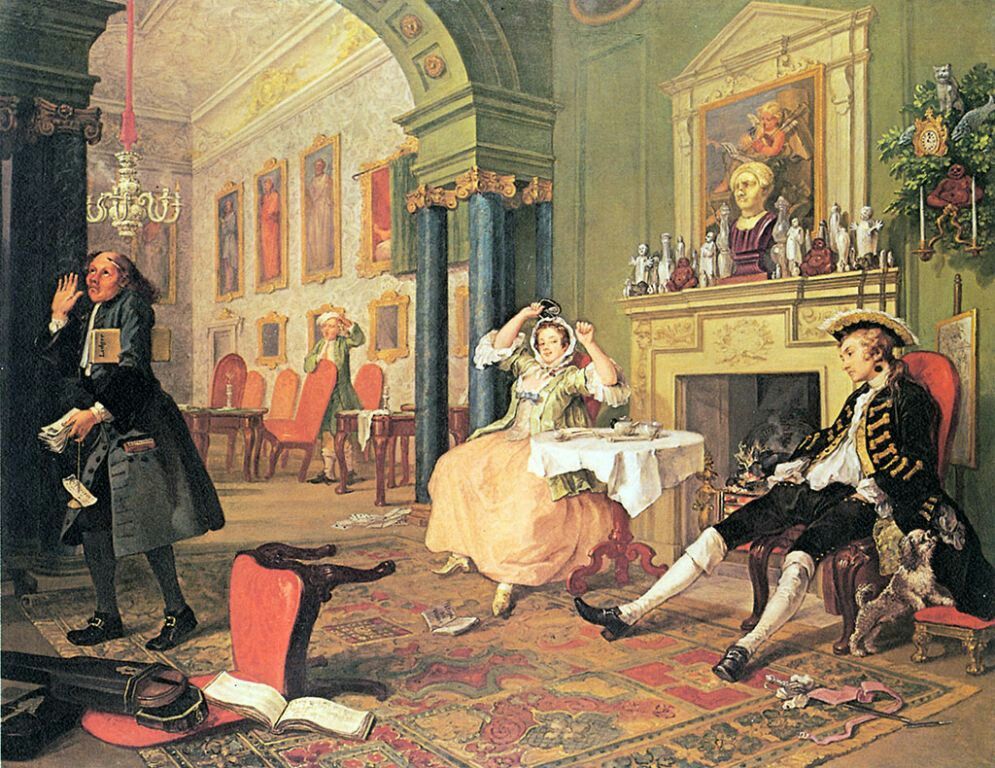

Another chapter that we did on the topic of Unrequited Love and Betrayal, which was an excuse to look at Lieder. So we look at the Lied, the art song, the song cycle, trying to see what that would tell us about the concept of love in the 19th century and how does that compare to modern times. What does it tell us about marriage as a social contract or as an economic institution? Since Lieder are fairly short, I chose a couple of representative things and an entire song cycle, the entire Dichterliebe. I tied that into Hogarth’s series of paintings, cynical paintings about marriage in the 19th century, Marriage à la mode. And then had a tangential discussion about women as property, and dowries, and all of that kind of stuff.

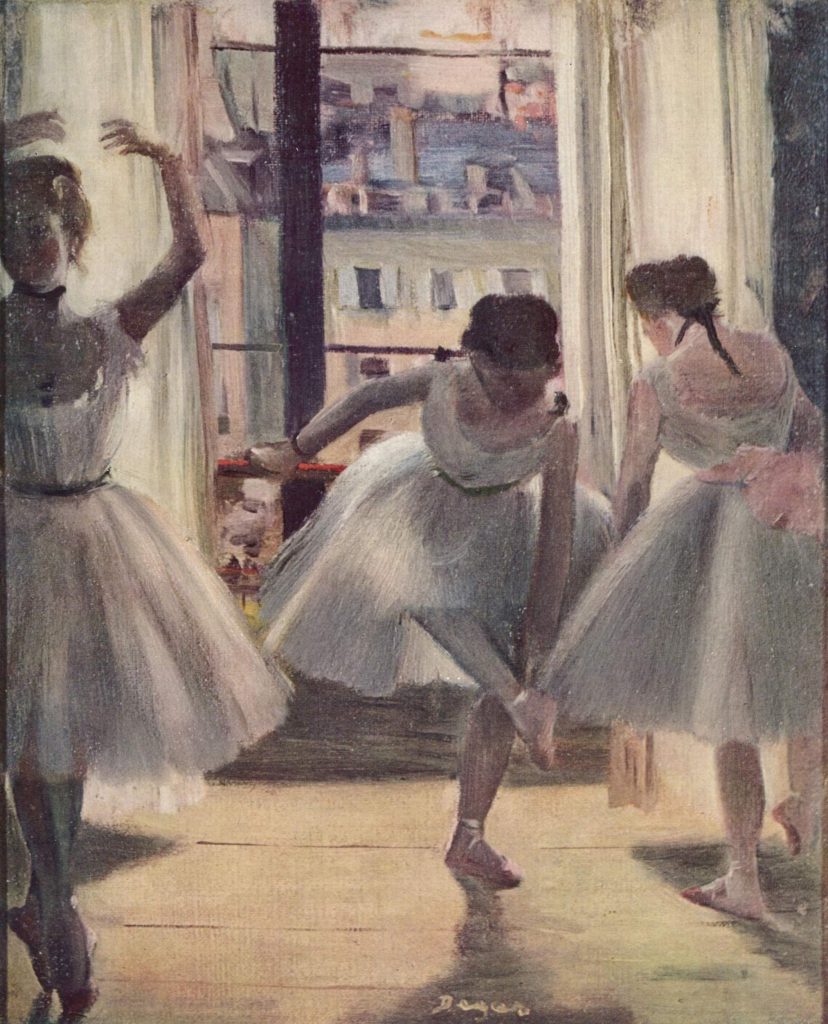

The third one that I did that I ended up loving was “Independent Women and 19th-Century Opera Verismo.” It was a good change to introduce opera as a genre to most people who think Phantom of the Opera is an opera. And talk about what opera is and how it changed to become opera verismo. Look at 19th-century attitudes about independent women as represented in music. Originally, I called this “Wild Women,” but I realized that actually sounded pejorative in and of itself. And what can studying each of these things tell us about the other. We looked at Carmen, which is fascinating unto itself. It was originally a cautionary tale: don’t be like Carmen. Nowadays it’s more like, “Nope, she did her own thing even though she paid a price.” And Puccini’s female characters in La bohème. We tied that into Degas’ The Dancers as a visual art piece.

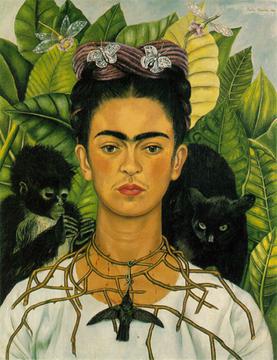

The very last one that we did toward the end of the semester, “Fate, Debauchery, and the Unholy.” This was an excuse to look at big choral/orchestral works from the 20th century, not sacred works, but secular pieces. Looking to see how it is different from sacred music, and what does this tell us about 20th-century concepts of sacred versus profane, for example. And the two pieces that tied into that, Carmina Burana and Bernstein’s Mass, which gave us a terrific opportunity to talk about the politics behind music, behind reception history, and things like that. And we tied that into a Frida Kahlo painting.

Those are four representative examples of how this can work, how you can bring in these tangential things and organize it around a theme. If I had gone chronologically for students who are only going to have one semester of a music history class, that is music appreciation, basically, because you can only scratch the surface and you never get to talk about what any of it means.

Does this non-chronological relieve you of the obligation to cover every genre, every period, all the big names?

Yes. And it’s hard to be okay with that until you remember that you whet the appetite, and they can dig in deeper on their own. For those students, it’s interesting, because an anthology commentary for a piece, for some of those students it will be a little too deep, for some of the students it’s not deep enough and they want to dig in further on their own, which is kind of neat. But rather than putting a watered-down two-paragraph superficial thing about Carmina Burana—this is sixty minutes of music with an enormous history behind it before Orff takes those materials and works with those texts in the 20th century. Two paragraphs aren’t going to cut it. For them to be able to dig in deeper and have access to that is great. I would rather have them, in fact, get in over their head and walk away enriched from it than have something that is too superficial. Most music appreciation textbooks, for example, it’s a page, page-and-a-half, of which 50% are graphics and things like that.

Do your students ever approach you after they’ve gone and looked at the commentaries or the articles and had more specific questions for you?

It does happen quite a lot, which I love. Not everybody is going to do that, but the student who is like, “What is this, because my interest is kind of piqued here?”—yeah, it does indeed happen. Sometimes it’s as simple as, “Am I understanding this correctly?”

Think about it from a folklorist perspective as taking ownership of something. If somebody spends six or seven days studying Schumann’s Dichterliebe, looking at the poetry behind it, and studying all the tangential stuff, they walk away feeling as though they’ve taken ownership of the piece. In a weird sense, it has kind of become a part of them. And when they hear it, they feel as if they understand it and they know it in a way they didn’t before. The ones who will say, “Oh yeah, I still have this on my playlist”—okay, she’s taken ownership of this.

Do you ever assign any of the articles in the Anthology or sections of them?

I do to music majors, especially. That’s super important. To the non-music majors, if I do assign an article, I will always come back and touch on it in class, because it’s like playing the lottery. You don’t know who is going to understand what. So the commentaries and articles serve very different purposes, but you kind of need both.

Some of the articles may be too technical for non-music majors, but you have to be okay with not understanding everything the first time if you want to learn more about something, right? There’s nobody who sits behind the wheel of a car for the first time knowing already how to drive. Occasionally I’ve had to say, “Don’t let this overwhelm you. This article is going to give you much more information than you need; be okay with that. Read it through the first time before class. Get out of it what you can get out.” My job will be to fill in the blanks.

Do you have any other specific examples or anecdotes of a time where something just really clicked with the students, with the class, about your syllabus?

A couple, and they were unexpected and way out in left field. One of the units, we looked at attitudes toward mental health. And we started out with Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb, which I don’t know if you are familiar with the piece, it’s based on a text that was written by a guy who was incarcerated in an insane asylum in the 19th century in London while he wrote it. And Britten took this and made this really beautiful piece out of it. The student that came up to me—I think it was just stream-of-consciousness, but they were just horrified that that recently, ideas about mental health should have been so horrific. They had something of a history with mental health issues—nothing cataclysmic, but more than zero—and thought, if I had been born in that period, I’d be locked up right now. I wasn’t expecting it, and I kind of felt like, was this beyond my pay grade here?

But honestly, every time a student comes up and says, “Oh my god, that was my favorite class,” somebody that I bump into on the street, or literally somebody who is taking my order at lunch a couple of months ago, things like that. I think, okay, that’s awesome, because at least this person has had her curiosity cultivated and hopefully will dig in more. And to repeat myself, society doesn’t need everybody to go out and become a professional-level musician, but society is certainly better off when everybody understands and appreciates the arts more, because it enriches everybody.

And a couple weeks ago, I got a random email from a student from several semesters back who had found on YouTube, heavy metal versions of early polyphony. This kid is a heavy metal guitar player. He came through as a classical guitar player. For some reason, classical guitar players all love heavy metal—I don’t know what that’s about. He was looking on YouTube for some of these pieces from class and he wanted to go back and listen to them again, and I was like, oh, okay. Good! I wasn’t expecting that.

Have you ever had your students read some of the material you’ve written for the Anthology?

I have. I’ve only actually written two commentaries. I’m in the middle of two other commentaries and a bio. I don’t know that anybody’s ever raised an eyebrow. I think they either think that I know everything or that I don’t know anything at all. There’s no clear in-between zone there. Nobody’s ever said, “Oh, you wrote this,” and I’ve never made a big point out of it.

I do stand by what I’ve written. The commentaries that I’ve written I felt need to be written in light of what we now understand about those particular works that we didn’t understand twenty years ago. If it meant that I needed to write them myself in order to make sure that they get into my students’ hands, then so be it.

Do you have any final advice for instructors that might be interested in utilizing the Anthology or other digital resources?

I think I would just say, if you check it out and find that it doesn’t necessarily have what you need, check back in six months, because it’s growing, it’s continuing. The beauty of an online digital resource is that there is no limit to how large it can be. I guess my advice would be if you don’t find what you need, check back.

I don’t have any colleagues at this point that don’t cherry-pick and take from multiple sources. So a source like the Anthology that’s designed to be cherry-picked from just makes sense to me.

In closing...

Listening to Scot talk about his thematic non-music history course was inspiring! The flexibility of the A-R Music Anthology is the perfect fit for bringing together different composers, periods, and genres in interesting ways. He will be teaching the course again in Spring 2022 and will be further refining it. We certainly look forward to checking back in with him about it in the future.

What new possibilities in your own teaching has this interview revealed to you? Have you tried something similar in your own classroom? Send us a message and share your experiences with ARMA. We love hearing from you!